Arte Contemporáneo visión universal: India y Costa Rica

Esta muestra anual MAYINCA, fue iniciada en Costa Rica en 2013, para celebrar el cambio de temporalidad mesoamericana o “Bactuk Maya”. Observa problemáticas actuales del arte originario prehispánico, filtrado por lo contemporáneo. Reflexiona acerca de procesos colonizadores y neo-hegemónicos que aún tensan aspectos políticos, comerciales, educativos y culturales, de ahí el subtítulo “Dinero Sucio”.

MAYINCA: Dirty Money. Museo P&T.

Portada del catálogo on line. Foto cortesía del artista.

“Universal Views” en la Galería No. 2, Escuela Artes Visuales IPS Academy of Art,

Indore, India. Foto cortesía de Amit Ganjoo.

Dirty Money. ARTSéum Zapote. Foto LFQ.

Fue inaugurada el 12 de octubre 2019, con dos exhibiciones simultáneas: “Universal Views” en la Galería No. 2, Escuela Artes Visuales IPS Academy of Art, ciudad de Indore, India; en “Museo del Pobre & Trabajador”, barriada popular de Ipís, Goicoechea, y el ARTséum, Zapote, Costa Rica.

MAYINCA: Dirty Money. Museo P&T. Foto cortesía del artista.

MAYINCA: Dirty Money. Museo P&T. Foto cortesía del artista.

MAYINCA: Dirty Money. Museo P&T. Rememora la Bienal de Lima 2003,

cuando Joaquín Rodríguez del Paso (1961-2016), presentó su performance “One Dollar”.

Exponer en un estudio-taller ubicado en un área subvertida por el degrado urbano, es punto de inflexión para el arte: Reivindica el territorio aproximando las manifestaciones críticas y creativas a la fuerza trabajadora, e impele a reflexionar acerca de flujos económicos, geopolítica, mercado global, capitalismo salvaje, paraísos fiscales, sustracción y trasiego de bienes artísticos, perspectivas donde se imponen nuevas tácticas filibusteras disfrazadas por el comercio.

Visos históricos que provienen desde la colonia, son memorias de piratería y otras presiones del poder. La vecina República de Panamá fue punto de partida para expedicionarios con sed de oro y valores artísticos extraídos de Perú y Mesoamérica; de ahí que hoy resuene en ejes del emporio mundial como “paraísos fiscales” (recuérdese la controversia de “Papeles de Panamá”).

MAYINCA: Dirty Money. Museo P&T. Foto cortesía del artista.

MAYINCA: Dirty Money. Museo P&T. Foto cortesía del artista.

MAYINCA: Dirty Money. Museo P&T. Foto cortesía del artista.

La curadora Virginia Pérez-Ratton (1950-2010), abordó estas contingencias históricas desde ángulos de visión y soportes reóricos para varios proyectos curatoriales, como la gran muestra “Estrecho Dudoso”, 2006, aprecia:

“La angostura de su geografía, bordeada por dos océanos que posibilitarían rutas ilimitadas, tienta al poder y a la codicia desde sus primeros tiempos. No en balde es Portobelo, el puerto construido bajo Felipe II en el Caribe panameño, la sede de ferias anuales donde confluyen centenares de mulas y tamemes cargados de expolio de la conquista, en ruta hacia el Viej Mundo”. (Pérez-Ratton. Virginia Pérez-Ratton. Centroamérica: Deseo de lugar. 2019. P.205)

MAYINCA: Dirty Money. Museo P&T. Foto cortesía del artista.

MAYINCA: Dirty Money. ARTSéum Zapote. Foto cortesía del artista.

MAYINCA: Dirty Money. ARTSéum Zapote. Foto cortesía del artista.

En el arte centroamericano el tema del dinero no es nuevo, para la Bienal de Lima 2003, Joaquín Rodríguez del Paso (1961-2016), uno de los artistas locales que más referencia al papel moneda como provocación, daba un dólar a quien hiciera un dibujo para su performance e instalación “One Dollar”. Otro de los artistas que trató el abordaje fue Rolando Castellón, quien se recuerda una estructura múltiple conformada por billetes costarricenses de cien colones, expuesta en “Rastros”, 2005, Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo.

Artistas y obras

Marcela Araya y José Rosales (Costa Rica), “No te amo”, 2015. Registra una experimentación con letras publicitarias en el techo de un edificio en Ciudad de México. “Al trasladarnos de territorio -comentan-, testimoniamos una fluctuación importante en el valor del capital material y humano, entre nuestro contexto y el visitado. En ambos casos existe un estado benefactor en declive acelerado, un incremento en la desigualdad y las economías informales.

Marcela Araya y José Rosales, “No te amo”, 2015.

”No te amo” reconoce el sentimiento de dislocación y desesperanza que nos envuelve, al reconocer que venimos de, y nos movemos hacia lugares castigados por las políticas neoliberales, que hacen posibles grandes despliegues publicitarios y que, sus restos materiales reutilizamos para expresar nuestra decepción”.

Ricardo Ávila, (Costa Rica) “El Agüisote”, 2019. La cultura popular inventa amuletos para que la suerte multiplique su dinero, guardándolo -como en este caso-, en una cerámica de la “Santa muerte”, fetiche de gran significación cultural. Al fondo aparece la reconocida marca de alta tecnología, generando un choque de idiosincrasias y estados sociales y comerciales.

Ricardo Ávila, “El Agüisote”, 2019.

Ricardo Ávila, (Costa Rica) “El Agüisote”, 2019. La cultura popular inventa amuletos para que la suerte multiplique su dinero, guardándolo -como en este caso-, en una cerámica de la “Santa muerte”, fetiche de gran significación cultural. Al fondo aparece la reconocida marca de alta tecnología, generando un choque de idiosincrasias y estados sociales y comerciales.

Carlos Barbarena de la Rocha “Políticos y dinero”, 2019.

Carlos Barbarena de la Rocha (Nicaragua), “Políticos y dinero”, 2019. Entre los políticos abunda el dinero producto de impuestos, que no siempre son bien administrados. Las riquezas del estado son acechadas por éstos quienes se frotan las manos ante un tesoro a desbaratar.

Maurizio Bianchi, “El dinero no huele” (PECVNIA NON OLET), 2019.

Maurizio Bianchi (Italia), “El dinero no huele” (PECVNIA NON OLET), 2019. El emperador Vespasiano observó que la orina recogida de los urinarios públicos de Roma, era vendida para obtener amoniaco, útil en el curtido del cuero, o para blanquear manchas en la ropa, por lo que impuso valor al recaudo. Suetonio, historiador romano reveló que Tito, hijo del emperador, reclamó a su padre la naturaleza del impuesto, y éste le mostró una moneda preguntándole si le ofendía el olor del oro.

Dinorah Carballo, “Judas”, 2019.

Dinorah Carballo (Costa Rica), “Judas”, 2019. La pieza alude al apóstol seguidor de Jesucristo, quien según la tradición judeo-cristiana traicionó al taumaturgo galileo, entregándolo a sus enemigos por treinta denarios. Un bolsito de tela es signo de su reflexión como dinero marcado, o sucio.

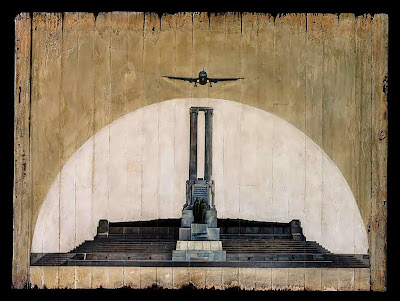

Juanma García, “Delayed Flight”, Sf.

Juanma García (Cuba-USA), “Delayed Flight”, Sf. Aborda el tema USA–Cuba en el contexto de la normalización de las relaciones que comenzaron en 2014, y que terminan peor de como estaban. El “Monumento a las victimas de Maine”, emplazado en el malecón habanero, y que la revolución socialista mutiló en 1961, cuando le fue derrumbada el águila de la cima de las columnas implica la reflexión: El águila nunca se repuso, y muchos auguran que hasta que no ocupe el lugar que tenía en el monumento, las relaciones entre ambos países seguirán mal. García ocupó el lugar vacío con un avión comercial, símbolo de la nueva águila en el emporio de la aeronáutica comercial.

Amit Ganjoo, “Dinero Negro”, 2019.

Amit Ganjoo (India), “Dinero Negro”, 2019. Explora un jardín de plantas cuyas flores son papel moneda, un paraíso de ensoñación, pero subvertido por la rosa negra, el “dinero negro”, signos inciertos en la economía actual. La flor se vuelve figura codiciada por su (in)existencia. Alude a un signo de interrogación, que cautiva a la literatura por el manejo semiótico del lenguaje, metáfora para su visión de mundo.

Irvin González, “Vacío”, 2019.

Irvin González (Costa Rica), “Vacío”, 2019. Pone en foco lo que puede significar este vocablo en tiempos de crisis, cuando las personas se lanzan al abismo por el vil metal, ante un sentimiento de vacío material, vacío espiritual, vacío profesional, y hasta político; pérdida de confianza en los gobernantes incapaces de generar la recuperación.

Diana Krevsky, “Parafiles dirty-money”. 2019

Diana Krevsky (USA), “Parafiles dirty-money”. Un cajero bancario es cuestionable por su higiene, en tanto es activado por tantas manos como personas lo usen, así como es el dinero sucio que dispensa. Es un signo de interrogación acerca de las relaciones interpersonales.

Illimani de los Andes, “La trinidad de Quetzalcóatl”, 2019

Illimani de los Andes (Nicaragua), “La trinidad de Quetzalcóatl”, 2019. La muerte y resurrección de Cristo representada en la trinidad, compone una “metáfora viviente”, que trasciende hacia la muerte y resurrección del símbolo mesoamericano de “Quetzalcóatl”, y pasa de una creencia a otra alcanzando noción de trinidad.

Carlos Lorenzana “Encuentra tu paraíso fiscal / Satisfacción garantizada”,

y “Males nuestros que estás en los pueblos”.

Carlos Lorenzana (Costa Rica), “Encuentra tu paraíso fiscal / Satisfacción garantizada”, y “Males nuestros que estás en los pueblos”. La situación de los paraísos fiscales es una realidad mundial, cada vez los adinerados disfrazan sus fortunas en estos territorios para evadir el pago de las cargas y/o tazas impositivas.

Bernardo Jaén Marques, “Mapas”, 2019

Bernardo Jaén Marques (Cuba-USA), “Mapas”, 2019. El artista reflexiona acerca de la territorialidad y política en los anales de la historia colonial del istmo, modificada por laudos y tratados entre los países que son tramas de discordia. En los primeros mapas al sur de Costa Rica (“Cofta Rica”) y norte de Panamá, aparecía el “Reino de Veragua” con status político de país. Hoy es tan solo una pequeña provincia panameña, y a Costa Rica, en 1941, le fue cercenada la región de Bocas del Toro para conformar Chiriquí.

Cildo Meirelles, “Intervención a 2 Reais”, S/f.

Cildo Meirelles (Brasil), “Intervención a 2 Reais”, S/f. Interviene “Dos Reais” del Banco de Brasil, y se apropia del valor, en tanto el papel por sí solo no vale nada, para decirnos que son los símbolos los que les cargan de contenido, y relativiza la imagen clásica de la deidad grecorromana que los ilustra, cambiándola por la de una mujer mestiza.

Iliana Moya, “Pepitas mas, pepitas menos", 2019.

Iliana Moya (Costa Rica), “Pepitas mas, pepitas menos", 2019. En Bolivia, los pobladores de reservas indígenas son desplazados y perseguidos. Trasciende que el presidente de ese país vendió a los chinos los derechos de explotación por 3.000 millones de dólares, cuya noticia circula en Europa calificada de ilegal. La artista instala cartografías de esas reservas donde se permite la caza y colecta de plantas de subsistencia, marcando las zonas en conflicto: Incendios, explotación y persecución de sus habitantes, y un globo terráqueo donde se aprecia que la mitad de ese país es parte de la selva amazónica. Al pie de los mapas, se exponen piedras pintadas de dorado, simulando pepitas de oro, pero embarrealadas y manchadas de sangre.

Moyo Coyatzine (Costa Rica). Varias intervenciones al espacio expositivo. El chamán de la cultura mesoamericana aprovecha cualquier espacio remanente para instalar sus percepciones del tema, como unos billetes y monedas enterradas, para reflexionar sobre el significado de éstos valores de cambio, portadores de suciedad u otros gérmenes políticos y sociales.

Zole Solano, Daniel y Tomás González (Costa Rica), “El amor de la abuela no tiene precio”, 2019. Dos niños regalan a su abuela paterna una memoria compuesta con fotografías de sus viajes a Tikal, Guatemala, para parodiar la publicidad de Master Card: “El Amor de la Abuela, No Tiene Precio”.

Zulay Soto, “Colectar Dinero Sucio”, 2019.

Zulay Soto (Costa Rica). “Colectar Dinero Sucio”, 2019. Aunque es mala educación por parte del pueblo rayar e ironizar escribiendo frases sucias en el papel moneda, la artista Zulay Soto colecciona este papel moneda, y realiza collages interviniéndolos con carga lúdica y cuestionamiento social.

Christian Salablanca (Costa Rica), “Llévame a la fama”, 2018. Él recoge y pide dinero a las personas de un precario suburbano. Lo recaudado es dinero ilícito, en tanto se usó para la compra de drogas o porque fue robado; lo acumula utilizando cinta adhesiva en la cual escribe: “Llévame a la fama”. Emplaza la manera de como muchos jóvenes buscan dinero fácil evadiendo obligaciones primarias, como estudiar o trabajar.

Christian Salablanca, “Llévame a la fama”, 2018.

Christian Salablanca (Costa Rica), “Llévame a la fama”, 2018. Él recoge y pide dinero a las personas de un precario suburbano. Lo recaudado es dinero ilícito, en tanto se usó para la compra de drogas o porque fue robado; lo acumula utilizando cinta adhesiva en la cual escribe: “Llévame a la fama”. Emplaza la manera de como muchos jóvenes buscan dinero fácil evadiendo obligaciones primarias, como estudiar o trabajar.

Othelo Quirval, ¿Cuál acumulado?, 2019.

Othelo Quirval (Costa Rica), ¿Cuál acumulado?, 2019. La lotería nacional juega en cada emisión “El Acumulado”. Millonario premio extraordinario que, si no sale, engrosa hasta premiar cuantiosas sumas. Sin embargo, es paradójico que la población gasta y gasta para probar suerte, y lo único que aumentan son esos fajos de papel que ya no valen nada.

Ernesto Pérez Ramírez, “Toten”. 2018.

Ernesto Pérez Ramírez (Costa Rica), “Toten”. 2018. Esta pintura en tela aprecia flujos paradójicos que nos sume en las mareas de la conciencia: Pueden representar al océano, al río, o a las riquezas que corren por las redes como transacciones lícitas, pero también al margen de la ley.

Edgar León (Costa Rica), “IZO Métrico Estructural”.

Edgar León (Costa Rica), “IZO Métrico Estructural”. La metáfora alude al trasiego de obras artísticas desde la colonia, y que aparecen en grandes colecciones en el mundo.

Hugo R. Vidal (Argentina), “No Hay un peso”.

Hugo R. Vidal (Argentina), “No Hay un peso”. La fotografía de un billete argentino parodia la volatilidad de la moneda de ese país sudamericano; problemática de la cual el mundo no está exento.

“Universal Views”

Trascendental, en la muestra tanto edifica un puente cultural entre India y Costa Rica: Mayinca se exhibe simultáneamente en Galería No. 2, Escuela de Artes Visuales IPS Academy en Indore. Interesa, en tanto la semilla germina al otro lado del planeta, abriendo nuevos surcos al pensamiento el cual motiva y reflexiona sobre la descolonización. En este aspecto, India, alberga un ámbito histórico común con el continente americano, de imposiciones hegemónicas durante importantes etapas de su acontecer. Amit Ganjoo, director de esa escuela y organizador “Miradas Universales”, expuso dobles de las obras generando un punto de itininerancia y colaboración, que visualice el arte de nuestras naciones. Pero, y aún más sustancial, significa abrir ventanas al acontecer en materia de arte actual, lo cual no solo informa, sino que forma a las generaciones de artistas.

Escuela de Artes Visuales de IPS Academy, Indore, India,

asiste el Ar. Achal K. Choudhary y Amit Ganjoo,

Importa considerar el fundamental aporte de la Escuela de Artes Visuales de IPS Academy, Indore, India, al Ar. Achal K. Choudhary y Amit Ganjoo, en tanto construye puentes culturales transversales entre países que tenemos en común una historia de colonización e imposiciones hegemónicas como ocurrió en India con la dominación inglesa. La distancia geográfico-cultural, política y lingúistica la rompe el arte, ofreciendo metodologías actuales para mirar los problemas y desventajas que nos acechan como países.

“Dirty Money” (AnonymA 020.2) en ARTSéum

La propuesta de ARTSéum Zapote, Costa Rica, media entre el anonimato en el arte contemporáneo, y traza un paralelismo con la reciente manifestación de arte efímero expuesta en los jardines de “Pitoes das Junias”, Portugal, la cual se extiende hasta junio de 2020. Suma a esta iniciativa de la Octava MAYINCA extender un mapa significativo “descolonizador” de los encuadres Manhatan-eurocéntricos y otras tácticas del poder.

Importa además considerar el fundamental aporte que representa la inclusión de la Escuerla de Artes Visuales de IPS Academy, Indore, India, en tanto construye puentes culturales transversales entre países que tenemos en común una historia de colonización e imposiciones hegemónicas como ocurrió en India con la dominación inglesa. La distancia geográfico-cultural, política y lingúistica la rompe el arte, ofreciendo metodologías actuales para mirar los problemas y desventajas que nos acechan como países.

Importa además considerar el fundamental aporte que representa la inclusión de la Escuerla de Artes Visuales de IPS Academy, Indore, India, en tanto construye puentes culturales transversales entre países que tenemos en común una historia de colonización e imposiciones hegemónicas como ocurrió en India con la dominación inglesa. La distancia geográfico-cultural, política y lingúistica la rompe el arte, ofreciendo metodologías actuales para mirar los problemas y desventajas que nos acechan como países.

Lo expuesto en ARTSéum, no deja de ofrecer una postura crítica, pero a la vez lúdica y jocosa de cuestionar, y ejercer el rol del arte de poner los puntos sobre las íes, clarificando a través de metáforas y otras figuras que motivan a la reflexión sobre estas problemáticas como la economía.

Museo de Pobre & Trabajador

Museo de Pobre & Trabajador

Cuestiona, entre otras críticas, a la cultura oficial, espacios y presupuestos de recursos públicos intangibles para la colectividad. El motivo gráfico identificador de “Dinero Sucio” proviene de la fotografía de un antiguo billete local de 50 colones, exhibido en el Museo Nacional de Costa Rica; presenta la particularidad de estar manchado de sangre. Interesa, en tanto lo instigado por el arte, y que en esas tensiones del mercado global, territorialidades, geopolítica, tráficos y economías salvajes, hay espinas y también corre la sangre.

MAYINCA: dirty money

Contemporary Art universal vision: India and Costa Rica

This annual MAYINCA sample, was initiated in Costa Rica in 2013, to celebrate the change of Mesoamerican temporality or "Bactuk Maya". Observe current problems of pre-Hispanic original art, filtered by the contemporary. Reflection on the colonizing and neohegemonic processes that still tense political, commercial, educational and cultural aspects, hence the subtitle "Dirty Money". It was inaugurated on October 12, 2019, with three simultaneous exhibitions: “Universal Views” in Gallery No. 2, IPS Visual Arts School of Art, City of Indore, India; in “Museo del Pobre & Trabajador”, popular neighborhood of Ipís, Goicoechea, and the ARTséum, Zapote, Costa Rica.

Exhibiting in a studio-workshop located in an area subverted by urban degradation, is a turning point for art: Claim the territory by approaching the critical and creative manifestations to the labor force, and impels to reflect on economic flows, geopolitics, market global, wild capitalism, tax havens, subtraction and transfer of artistic goods, perspectives where new filibuster tactics disguised by trade are imposed.

Historical visions that come from the colony, are memories of piracy and other pressures of power. The neighboring Republic of Panama was a starting point for expeditionaries with a thirst for gold and artistic values extracted from Peru and Mesoamerica; Hence, today it resonates in axes of the world emporium as "tax havens" (remember the controversy of "Papers of Panama").

The curator Virginia Pérez-Ratton (1950-2010), addressed these historical contingencies from viewing angles and rhetorical supports for several curatorial projects, such as the great sample “Doubtful Strait”, 2006, appreciates:

“The narrowness of its geography, bordered by two oceans that would allow unlimited routes, tempts power and greed from its earliest times. Not in vain is Portobelo, the port built under Felipe II in the Panamanian Caribbean, the headquarters of annual fairs where hundreds of mules and tamemes loaded with pillage of the conquest converge, en route to the Old World. ” (Pérez-Ratton. Virginia Pérez-Ratton. Central America: Desire for a place. 2019. P.205)

In Central American art, the issue of money is not new, for the 2003 Biennial of Lima, Joaquín Rodríguez del Paso (1961-2016), one of the local artists who most referred to paper money as provocation, gave a dollar to anyone who made a drawing for its performance and installation "One Dollar". Another of the artists who tried the approach was Rolando Castellón, who remembers a multiple structure made up of one hundred colón Costa Rican bills, exhibited in “Rastros”, 2005, Museum of Contemporary Art and Design.

Artists and works

Marcela Araya and José Rosales (Costa Rica), “I don't love you”, 2015. Record an experiment with advertising letters on the roof of a building in Mexico City. “When moving from territory - they comment -, we testify an important fluctuation in the value of the material and human capital, between our context and the visited one. In both cases there is a benefactor state in accelerated decline, an increase in inequality and informal economies. "I do not love you" recognizes the feeling of dislocation and hopelessness that surrounds us, recognizing that we come from, and move towards places punished by neoliberal policies, that make possible large advertising displays and that, its material remains we reuse to express our disappointment "

Ricardo Ávila, (Costa Rica) “El Agüisote”, 2019. Popular culture invents charms so that luck multiplies its money, keeping it - as in this case - in a pottery of the “Santa Muerte”, a fetish of great cultural significance . In the background appears the renowned high-tech brand, generating a clash of idiosyncrasies and social and commercial states.

Carlos Barbarena de la Rocha (Nicaragua), “Politicians and money”, 2019. Among politicians, money from taxes is abundant, which is not always well managed. The wealth of the state is stalked by these who rub their hands before a treasure to be thwarted.

Maurizio Bianchi (Italy), “Money does not smell” (PECVNIA NON OLET), 2019. Emperor Vespasian observed that urine collected from public urinals in Rome was sold to obtain ammonia, useful in tanning leather, or to whiten stains on clothes, so it imposed value on collection. Suetonio, Roman historian revealed that Tito, son of the emperor, demanded from his father the nature of the tax, and he showed him a coin asking if he was offended by the smell of gold.

Dinorah Carballo (Costa Rica), “Judas”, 2019. The piece refers to the apostle following Jesus Christ, who according to Judeo-Christian tradition betrayed the Galilean caster, delivering him to his enemies for thirty denarii. A cloth bag is a sign of your reflection as money marked, or dirty.

Juanma García (Cuba-USA), “Delayed Flight”, Sf. It addresses the USA-Cuba issue in the context of the normalization of relations that began in 2014, and that end worse than they were. The "Monument to the victims of Maine", located on the Havana seawall, and that the socialist revolution mutilated in 1961, when the eagle from the top of the columns was collapsed implies reflection: The eagle never recovered, and many predict that until he occupies the place he had in the monument, relations between the two countries will continue badly.

García occupied the empty place with a commercial airplane, symbol of the new eagle in the emporium of commercial aeronautics.

Amit Ganjoo (India), “Black Money”, 2019. Explore a garden of plants whose flowers are paper money, a dream paradise, but subverted by the black rose, the “black money”, uncertain signs in today's economy. The flower becomes a coveted figure for its (in) existence. It refers to a question mark, which captivates literature by the semiotic handling of language, a metaphor for its worldview.

Irvin González (Costa Rica), “Vacuum”, 2019. It puts in focus what this word can mean in times of crisis, when people are thrown into the abyss by the vile metal, before a feeling of material emptiness, spiritual emptiness, emptiness professional, and even political; loss of confidence in rulers unable to generate recovery.

Diana Krevsky (USA), "Paraffiles dirty-money". A bank teller is questionable for its hygiene, as long as it is activated by as many hands as people use it, as is the dirty money it dispenses. It is a question mark about interpersonal relationships.

Illimani de los Andes (Nicaragua), “The trinity of Quetzalcoatl”, 2019. The death and resurrection of Christ represented in the trinity, composes a “living metaphor”, which transcends towards the death and resurrection of the Mesoamerican symbol of “Quetzalcóatl”, and it goes from one belief to another reaching notion of trinity.

Carlos Lorenzana (Costa Rica), "Find Your Tax Paradise / Satisfaction Guaranteed", and "Our Bad You Are in the Villages". The situation of tax havens is a worldwide reality, every time the wealthy disguise their fortunes in these territories to evade the payment of charges and / or tax rates.

Bernardo Jaén Marques (Cuba-USA), “Maps”, 2019. The artist reflects on territoriality and politics in the annals of the colonial history of the isthmus, modified by awards and treaties between countries that are plots of discord. In the first maps to the south of Costa Rica (“Cofta Rica”) and northern Panama, the “Kingdom of Veragua” appeared with the country's political status. Today it is only a small Panamanian province, and in Costa Rica, in 1941, the Bocas del Toro region was severed to form Chiriquí.

Cildo Meirelles (Brazil), “Intervention at 2 Reais”, S / f. “Dos Reais” from the Bank of Brazil intervenes, and appropriates the value, while the paper alone is worth nothing, to tell us that it is the symbols that load them with content, and relativizes the classic image of the Greco-Roman deity that he illustrates them, changing it to that of a mestizo woman.

Iliana Moya (Costa Rica), “Cartographies of Discord”, 2019. In Bolivia, the inhabitants of indigenous reserves are displaced and persecuted. It transpires that the president of that country sold the exploitation rights to the Chinese for 3 billion dollars, whose news circulates in Europe classified as illegal. The artist installs cartographies of these reserves where hunting and collection of subsistence plants are allowed, marking the areas in conflict: Fire, exploitation and persecution of its inhabitants, and a globe where it is appreciated that half of that country is part of the Amazon jungle. At the bottom of the maps, gold-painted stones are exposed, simulating gold nuggets, but muddy and bloodstained.

Moyo Coyatzine (Costa Rica). Several interventions to the exhibition space. The shaman of the Mesoamerican culture takes advantage of any remaining space to install his perceptions of the subject, such as notes and buried coins, to reflect on the meaning of these exchange values, bearers of dirt or other political and social germs.

Zole Solano, Daniel and Tomás González (Costa Rica), “Grandma's love is priceless”, 2019. Two children give their paternal grandmother a memory composed of photographs of their trips to Tikal, Guatemala, to parody the advertising of Master Card: "Grandma's Love, It's Priceless."

Zulay Soto (Costa Rica). “Collect Dirty Money”, 2019. Although it is bad education on the part of the people to scratch and ironize writing dirty sentences on paper money, the artist Zulay Soto collects this paper money, and makes collages intervening them with playful load and social questioning.

Christian Salablanca (Costa Rica), "Take Me to Fame", 2018. He collects and asks for money from the people of a precarious suburban. The proceeds are illicit money, as long as it was used to buy drugs or because it was stolen; he accumulates it using adhesive tape in which he writes: "Take me to fame." It begins the way many young people look for easy money by avoiding primary obligations, such as studying or working.

Othelo Quirval (Costa Rica), Which one accumulated ?, 2019. The national lottery plays in each issue “The Accumulated”. Millionaire extraordinary prize that, if it does not come out, thickens up to reward large sums. However, it is paradoxical that the population spends and spends to try their luck, and the only thing that increases is those wads of paper that are worthless.

Ernesto Pérez Ramírez (Costa Rica), "Toten". 2018. This canvas painting appreciates paradoxical flows that add us to the tides of conscience: They can represent the ocean, the river, or the riches that run through the networks as licit transactions, but also outside the law.

Edgar León (Costa Rica), “Structural Metric IZO”. The metaphor refers to the transfer of artistic works from the colony, and they appear in large collections in the world.

Hugo R. Vidal (Argentina), "There is no weight." The photograph of an Argentine ticket parodies the volatility of the currency of that South American country; problematic from which the world is not exempt.

Laura Elena Ortíz

Art is for all ages and is pleased that both older adult artists and children participate, as there are no limits to understand the problems that make up humanity. In this case, a Mexican girl of ten years shares her drawing of a paper money.

“Universal Views”

Transcendental, in the exhibition both builds a cultural bridge between India and Costa Rica: Mayinca is exhibited simultaneously in Gallery No. 2, IPS Academy School of Visual Arts in Indore. Interesting, while the seed germinates on the other side of the planet, opening new grooves to thought which motivates and reflects on decolonization. In this regard, India is home to a common historical area with the American continent, of hegemonic impositions during important stages of its occurrence. Amit Ganjoo, director of that school and organizer “Universal Looks”, exhibited doubles of the works generating a point of itinerancy and collaboration, which visualizes the art of our nations. But, and even more substantial, it means opening windows when it comes to current art, which not only informs, but also shapes the generations of artists.

It is important to consider the fundamental contribution of the Academy of Visual Arts of the IPS Academy, Indore, India, to Ar. Achal K. Choudhary and Amit Ganjoo, while building cross-cultural cultural bridges between countries that have in common a history of hegemonic colonization and impositions as in India with English domination. The geographical-cultural, political and linguistic distance is broken by art, the current methodologies to look at the problems and disadvantages that haunt us as countries.

“Dirty Money” (AnonymA 020.2) in ARTSéum

The proposal of ARTSéum Zapote, Costa Rica, mediates between anonymity in contemporary art, and draws a parallel with the recent manifestation of ephemeral art exhibited in the gardens of “Pitoes das Junias”, Portugal, which runs until June 2020 Add to this initiative of the Eighth MAYINCA to extend a significant “decolonizing” map of Manhatan-Eurocentric frames and other power tactics.

It is also important to consider the fundamental contribution of the inclusion of the School of Visual Arts of the IPS Academy, Indore, India, as it builds cross-cultural cultural bridges between countries that have in common a history of colonization and hegemonic impositions as happened in India with domination English The geographical-cultural, political and linguistic distance is broken by art, offering current methodologies to look at the problems and disadvantages that haunt us as countries.

The exposed in ARTSéum, does not stop offering a critical posture, but at the same time playful and joking to question, and exercise the role of the art of putting the points on the ies, clarifying through metaphors and other figures that motivate the reflection about these problems like the economy.

Poor & Worker Museum

It questions, among other criticisms, the official culture, spaces and budgets of intangible public resources for the community. The graphic motif that identifies “Dirty Money” comes from the photograph of an old local 50-colón bill, displayed in the National Museum of Costa Rica; It has the peculiarity of being stained with blood. Interesting, as instigated by art, and that in these tensions of the global market, territorialities, geopolitics, traffic and wild economies, there are thorns and blood also runs.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario